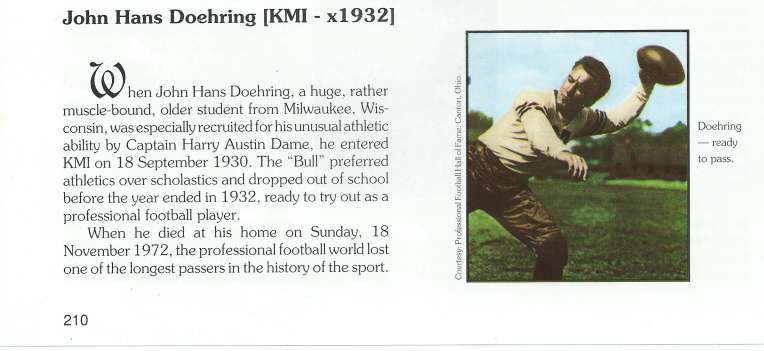

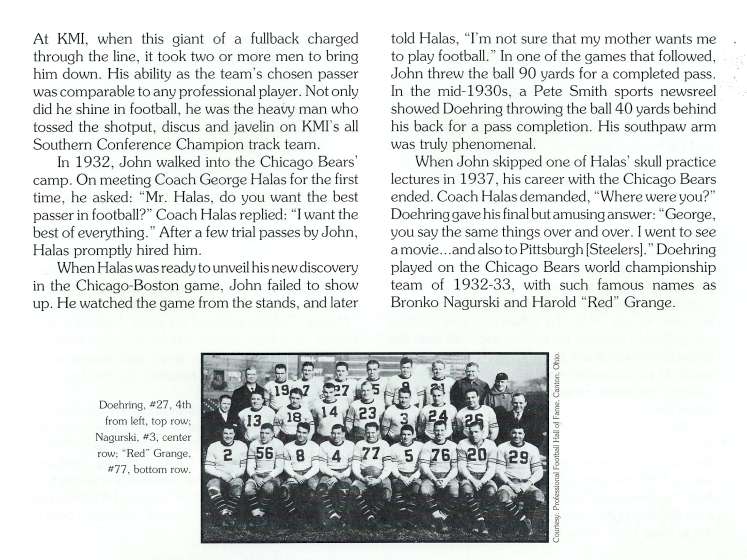

John Doehring, x'32 |

|

REFLECTIONS: A Portrait - Biography of the Kentucky Military Institute (1845 - 1971), pages 210-211 by James Darwin Stephens |

|

Forward

Passing, Behind the Back In

N.F.L.’s Early Days, John Doehring Was a Passing Sideshow in the

Chicago Bears’ Circus Act By

DAN DALY, Published: September 15, 2012 One

good reason is that newspaper coverage was sparse in the first few

decades; there simply wasn’t much reported beyond the games. So it is

hard to get a real feel for what pro football was like in that period —

and even harder to learn much about the players and personalities who

helped lift the league out of the primordial swamp. Good

luck, for instance, finding an article in any 1930s publication about

John Doehring, a Chicago Bears quarterback

known as Bull, who could fling the ball behind his back more than half

the length of the field. To fill this void, I spent two decades

researching and reading everything I could get my hands on about the

N.F.L.’s first half-century: long-ago-published books, newspaper

microfilm, archival material at the Pro Football Hall of Fame — and

interviewing scores of former players. What

I learned is that the first

50 years was an era of ideas. In 1929, the Orange Tornadoes thought it

would be cool to put letters on jerseys instead of numbers. In 1942,

Packers Coach Curly Lambeau kept his substitutes in the nice, warm

locker room, instead of on the sideline in frigid Green Bay. In 1950,

an aspiring N.F.L. owner proposed building an indoor stadium in

Houston, long before the Astrodome became a reality. The

decades since have been entertainingly anticlimactic. Once the American

Football League merged with the N.F.L. in 1970, everything changed.

When a sport ceases to have competition, it loses something — its

creative edge, maybe. And that breeds conservatism. The

league moves so slowly these days that it took about four decades to

fix the flawed overtime rules. If the A.F.L. were still around,

prodding the N.F.L. into being better, the correction would have come

much sooner. At

a time when passing attacks were still fairly primitive, Doehring’s

throws had an almost Sputnik-like quality about them. He wasn’t a great

player by any stretch, but he had one great talent — and the Bears

patriarch, George Halas, was smart enough to see it could be put to

use. Doehring could do more than just help the team win games; he could

be a sideshow, somebody who could entertain the fans with his

freakishly strong arm. He

was never more of a circus act than when the Bears barnstormed around

the country. During a workout in Los Angeles in January 1934, Doehring

uncorked a 70-yard pass to Bill Hewitt and “experienced the strange

sensation of hearing a wave of hand-clapping,” The Chicago Tribune

reported. Doehring was a product of

the Milwaukee sandlots who at 23 had decided to give pro football a

shot after failing his entrance exam to the University of Wisconsin. He

just showed up at a Bears practice in the middle of the 1932 season and

talked his way into a tryout. By the end of the week, he was suiting up

against the Portsmouth Spartans. “He

threw the ball so hard, nobody could catch it,” Ookie Miller, the

center on those Bears clubs, told me in the 1990s. “He gave Luke

Johnson a sore chest because it went right through his hands and hit

him in the chest.” Another

teammate, halfback Ray Nolting, said, “That son of a gun could throw a

ball 60 yards behind his back — accurately.” If

only Doehring had thrown a behind-the-back pass for a touchdown in an

actual N.F.L. game. Alas, it never happened. (That was not hard to

confirm because Doehring threw only seven touchdown passes in his

six-year career.) In

his 1947 book, “The Chicago Bears,” Howard

Roberts wrote that Doehring zipped a behind-the-back pass to Johnson in

a 1934 rout of Cincinnati but that Johnson dropped it in the end zone.

The only problem is George Strickler didn’t mention it in his article

for The Chicago Tribune — and Strickler didn’t get into the writer’s

wing of the Pro Football Hall of Fame by omitting such details. Doehring

definitely threw a behind-the-back touchdown pass on the barnstorming

trail, though. (What else was there to do in lopsided games?) The

Associated Press’s account of a January 1938 exhibition in New Orleans

ended with this line: “John Doehring, sensational southpaw passer for

the Bears, flipped one behind his back to Lester McDonald for 25 yards

and the pro team’s final touchdown as the Bears made a show of the

game.” Pro

football may never again be as fascinating as it was from the 1920s to

the ’60s. The N.F.L. is concerned with maintaining success now,

protecting everybody’s investment. In the salad days, when there was

less to lose, people were more willing to experiment — with lots of

things, just about anything. Doehring,

for instance, followed the lead of the Bears star Bronko Nagurski and

moonlighted as a pro wrestler, as did plenty of other N.F.L. players of

that era. He also played on a baseball team run by Happy Felsch, one of the

eight White Sox barred from the big leagues for throwing the 1919 World

Series. But

Doehring’s greatest gift was for wrapping his fingers around a ball and

letting it fly. In such moments, he could inspire awe. After

receiving a glimpse of Doehring’s behind-the-back act in 1937, Braven

Dyer of The Los Angeles Times wrote: “He attained this dexterity

without the aid of a college education. Had he received the benefits of

higher learning, he might be able to throw a curve which would come

back to him.” This

article is adapted from “The National Forgotten League: Entertaining

Stories and Observations from Pro Football’s First Fifty Years” by Dan

Daly, by permission of the University of Nebraska Press. It has always amazed me how little literary attention has been paid to professional football’s early days. Baseball historians have put the game under a microscope. There is probably a book out there that will tell you what Babe Ruth ate for breakfast on the day he swatted his 714th home run. The story of the N.F.L.’s formative years, on the other hand, is still largely untold.

Provided by Cappy

Gagnon |